INSULIN PROTECTS CANCER CELLS FROM APOPTOSIS

Insulin can promote the growth and survival of cancer cells. Here’s how:

1. Insulin promotes cell growth and proliferation: Insulin is a hormone that regulates glucose metabolism and promotes the uptake of glucose into cells. Cancer cells have a high demand for glucose to fuel their rapid growth and proliferation. Insulin stimulates the uptake of glucose into cancer cells, providing them with the energy and nutrients they need to grow and divide.

2. Insulin activates signaling pathways: Insulin activates signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, which are involved in cell growth, survival, and metabolism. Dysregulation of these pathways is commonly observed in cancer cells and contributes to their uncontrolled growth. Insulin can enhance the activity of these pathways in cancer cells, promoting their survival and proliferation.

3. Insulin increases insulin-like growth factor (IGF) levels: Insulin can stimulate the production of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), particularly IGF-1. IGFs are growth factors that can bind to receptors on cancer cells and promote their growth and survival. Elevated levels of IGF-1 have been associated with an increased risk of various cancers.

4. Insulin reduces apoptosis: Apoptosis is a programmed cell death process that helps eliminate damaged or abnormal cells, including cancer cells. Insulin can inhibit apoptosis in cancer cells, allowing them to evade cell death and continue to proliferate.

5. Insulin promotes inflammation: Chronic inflammation is a hallmark of cancer development and progression. Insulin can contribute to inflammation by activating inflammatory signaling pathways and promoting the release of pro-inflammatory molecules. Inflammation creates a favorable environment for cancer growth and can support tumor angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis.

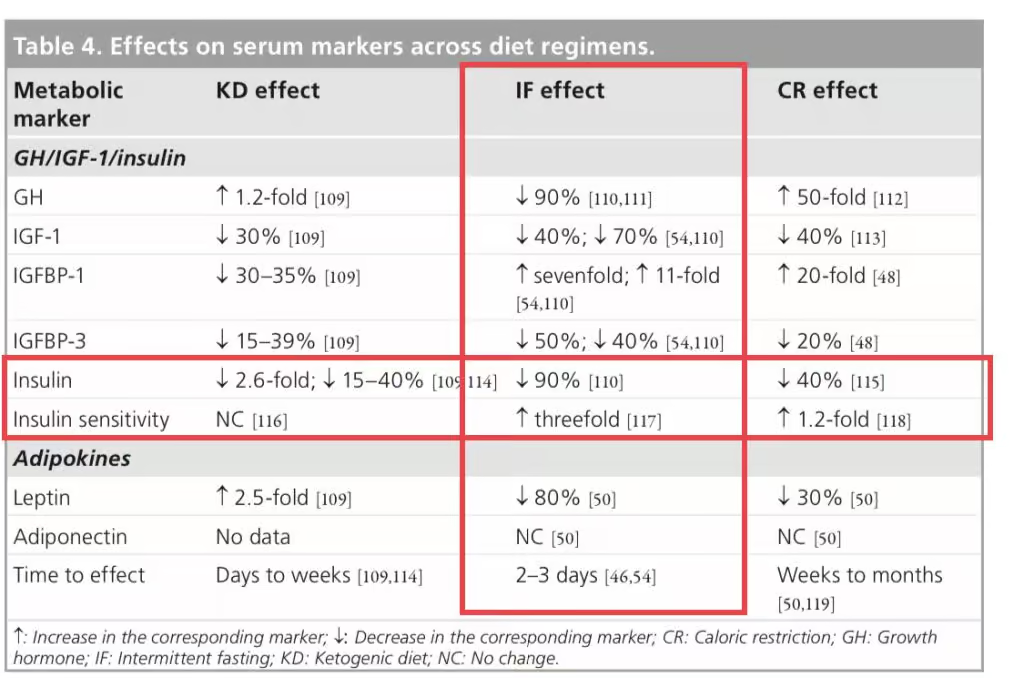

It’s important to note that insulin itself is not the sole factor in cancer development and progression. Other factors, such as genetic mutations, lifestyle factors, and other hormones, also play significant roles. However, the relationship between insulin and cancer highlights the potential impact of metabolic factors on cancer development and suggests that strategies to reduce insulin levels, such as dietary interventions, may have therapeutic benefits in cancer treatment.

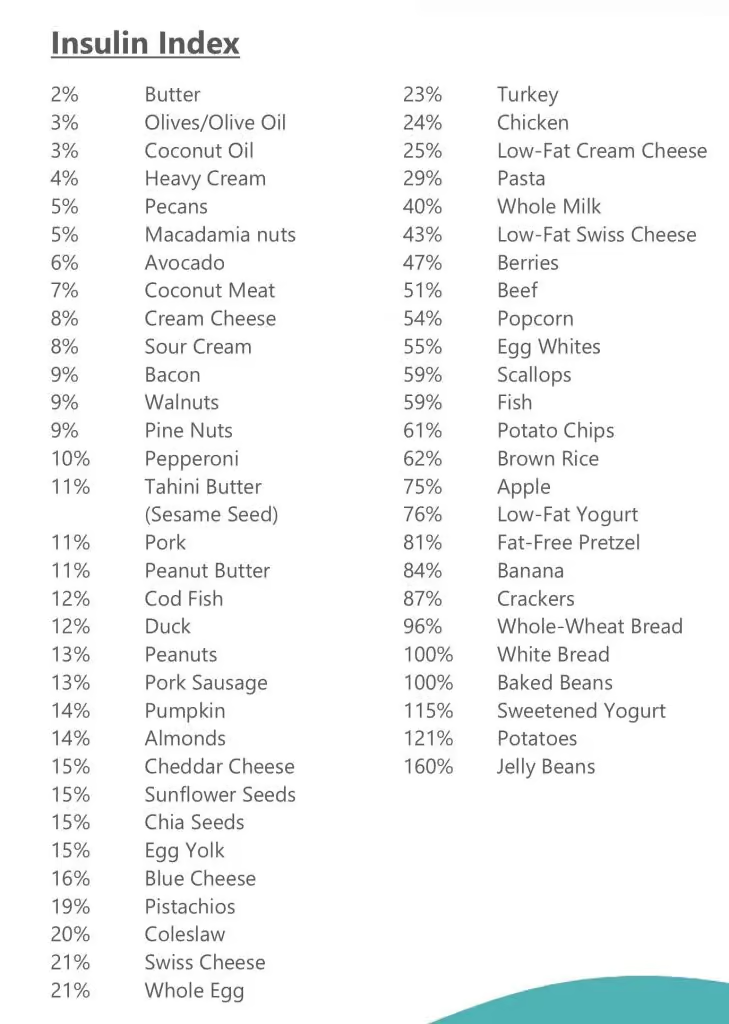

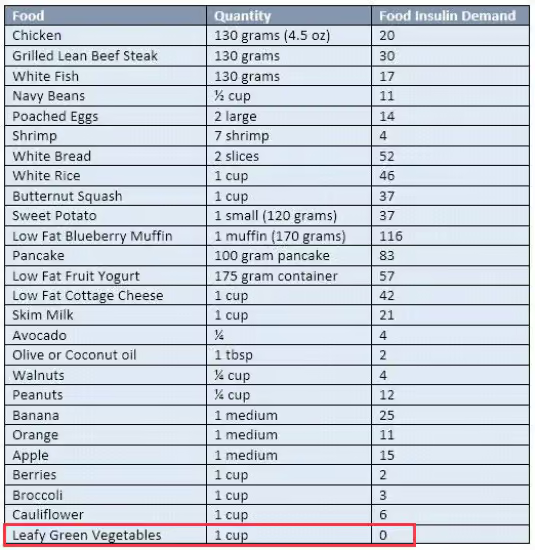

If you are serious about beating and preventing cancer then you want to be secreting as little insulin as possible while remaining as insulin sensitive as possible. That means you only want a tiny amount of insulin being utilized to maintain healthy blood sugar levels.

How?

Simple! 22/2 daily intermittent fasting with blends and strict non dairy paleo keto LOW INSULIN INDEX diet.

| Low Insulin Foods | Insulin index | Glycemic Index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endive | 10 | 10 | 1.25 | 0.2 | 3.35 |

| Sorrel | 10 | 10 | 2 | 0.7 | 3.2 |

| Chives | 10 | 10 | 3.27 | 0.73 | 4.35 |

| Brown champignons | 10 | 15 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 4.3 |

| Champignons | 10 | 15 | 3.09 | 0.34 | 3.26 |

| Champignons (boiled) | 10 | 15 | 2.17 | 0.47 | 5.29 |

| Garlic | 10 | 30 | 6.36 | 0.5 | 33.06 |

| Lemon peel | 10 | 20 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 16 |

| Orange peel | 10 | 20 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 25 |

| Cauliflower | 10 | 10 | 1.92 | 0.28 | 4.97 |

| Cauliflower (boiled) | 10 | 10 | 1.84 | 0.45 | 4.11 |

| Dill dried | 10 | 10 | 19.96 | 4.36 | 55.82 |

| Dill | 10 | 10 | 3.46 | 1.12 | 7.02 |

| Thyme | 10 | 10 | 5.56 | 1.68 | 24.45 |

| Asparagus | 10 | 15 | 2.2 | 0.12 | 3.88 |

| Asparagus (boiled) | 10 | 15 | 2.4 | 0.22 | 4.11 |

| Celery | 10 | 10 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 2.97 |

| Red lettuce | 10 | 10 | 1.33 | 0.22 | 2.26 |

| Butter lettuce | 10 | 10 | 1.35 | 0.22 | 2.23 |

| Сornsalad | 10 | 10 | 2 | 0.4 | 3.6 |

| Ruccola | 10 | 10 | 2.58 | 0.66 | 3.65 |

| Rosemary | 10 | 10 | 3.31 | 5.86 | 20.7 |

| Radikkyo | 10 | 15 | 1.43 | 0.25 | 4.48 |

| Портулак | 10 | 10 | 2.03 | 0.36 | 3.39 |

| Tomatoes | 10 | 10 | 0.88 | 0.2 | 3.89 |

| Parsley dried | 10 | 10 | 26.63 | 5.48 | 50.64 |

| Parsley | 10 | 10 | 2.97 | 0.79 | 6.33 |

| Chili pepper red hot | 10 | 15 | 1.87 | 0.44 | 8.81 |

| Bulgarian pepper | 10 | 15 | 0.86 | 0.17 | 4.64 |

| Pecan | 10 | 10 | 9.17 | 71.97 | 13.86 |

| Macadamia Nut | 10 | 10 | 7.91 | 75.77 | 13.82 |

| Oregano | 10 | 10 | 9 | 4.28 | 68.92 |

| Opuntia (leaves) | 10 | 10 | 1.32 | 0.09 | 3.33 |

| Peppermint | 10 | 10 | 3.75 | 0.94 | 14.89 |

| Mint fresh | 10 | 10 | 3.29 | 0.73 | 8.41 |

| Marjoram | 10 | 10 | 12.66 | 7.04 | 60.56 |

| Shallot | 10 | 15 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 16.8 |

| Leeks | 10 | 15 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 14.15 |

| Bunching onion | 10 | 10 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 6.5 |

| Red onions (sweet onions) | 10 | 10 | 0.8 | 0.08 | 7.55 |

| Onions | 10 | 10 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 9.34 |

| Green onions | 10 | 10 | 0.97 | 0.47 | 5.74 |

| Chicory leaves | 10 | 10 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 4.7 |

| Pumpkin leaves | 10 | 10 | 3.15 | 0.4 | 2.33 |

| Dandelion leaves | 10 | 10 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 9.2 |

| Amaranth leaves | 10 | 10 | 2.46 | 0.33 | 4.02 |

| Lemongrass | 10 | 10 | 1.82 | 0.49 | 25.31 |

| Saltbush | 10 | 10 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 7.3 |

| Cress Salad | 10 | 15 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 5.5 |

| Cypress | 10 | 10 | 4.71 | 2.75 | 19.22 |

| Cilantro (coriander leaves) | 10 | 10 | 2.13 | 0.52 | 3.67 |

| Savoy cabbage | 10 | 10 | 2 | 0.1 | 6.1 |

| Peking cabbage | 10 | 10 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 2.18 |

| Kale | 10 | 10 | 3.02 | 0.61 | 5.42 |

| Sauerkraut cooked (boiled) | 10 | 10 | 2.71 | 0.72 | 5.65 |

| Curly cabbage raw | 10 | 10 | 4.28 | 0.93 | 8.75 |

| Red cabbage | 10 | 10 | 1.43 | 0.16 | 7.37 |

| Cabbage fresh white | 10 | 15 | 1.28 | 0.1 | 5.8 |

| Cabbage boiled (white cabbage) | 10 | 15 | 1.27 | 0.06 | 5.51 |

| Brussels sprouts (boiled) | 10 | 15 | 2.55 | 0.5 | 7.1 |

| Broccoli (boiled) | 10 | 10 | 2.38 | 0.41 | 7.18 |

| Whitetail (boiled) | 10 | 10 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 2.16 |

| Jerucha | 10 | 10 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 1.29 |

| Enoki mushrooms | 10 | 15 | 2.66 | 0.29 | 7.81 |

| Shiitake mushrooms | 10 | 15 | 2.24 | 0.49 | 6.79 |

| Morels mushrooms | 10 | 15 | 3.12 | 0.57 | 5.1 |

| Portobello mushrooms | 10 | 15 | 2.11 | 0.35 | 3.87 |

| Maitake mushrooms | 10 | 15 | 1.94 | 0.19 | 6.97 |

| Chanterelle mushrooms | 10 | 15 | 1.49 | 0.53 | 6.86 |

| Oyster mushrooms | 10 | 15 | 3.31 | 0.41 | 6.09 |

| Brussels sprouts | 10 | 15 | 3.38 | 0.3 | 8.95 |

| Broccoli raab | 10 | 10 | 3.17 | 0.49 | 2.85 |

| Chinese broccoli | 10 | 10 | 1.2 | 0.76 | 4.67 |

| Broccoli | 10 | 10 | 2.82 | 0.37 | 6.64 |

| Beet | 10 | 10 | 2.2 | 0.13 | 4.33 |

| Turnip tops | 10 | 10 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 7.13 |

| Whitetail | 10 | 10 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 3.61 |

| Eggplant | 10 | 40 | 0.98 | 0.18 | 5.88 |

| Basil | 10 | 10 | 3.15 | 0.64 | 2.65 |

SCIENCE

“We report here that insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) fully protect HT29-D4 colon carcinoma cell”

Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Protects Colon Cancer Cells from Death Factor-induced Apoptosis by Potentiating Tumor Necrosis Factor α-induced Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase and Nuclear Factor κB Signaling Pathways

The role of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) in programmed cell death has been investigated in vivo in a biodiffusion chamber, where the extent of cell death could be determined quantitatively. We found that a decrease in the number of IGF-IRs causes massive apoptosis in vivo in several transplantable tumors, either from humans or rodents. Conversely, an overexpressed IGF-IR protects cells from apoptosis in vivo. We also show that the same conditions that in vitro cause only partial growth arrest with a minimum of cell death, induce in vivo almost complete cell death. We conclude that the IGF-IR activated by its ligands plays a very important protective role in programmed cell death, and that its protective action is even more striking in vivo than in vitro

The Insulin-like Growth Factor I Receptor Protects Tumor Cells from Apoptosis in Vivo

Insulin‐like growth factor (IGF)‐I protects many cell types from apoptosis. As a result, it is possible that IGF‐I‐responsive cancer cells may be resistant to apoptosis‐inducing chemotherapies. Therefore, we examined the effects of IGF‐I on paclitaxel and doxorubicin‐induced apoptosis in the IGF‐I‐responsive breast cancer cell line MCF‐7. Both drugs caused DNA laddering in a dose‐dependent fashion, and IGF‐I reduced the formation of ladders. We next examined the effects of IGF‐I and estradiol on cell survival following drug treatment in monolayer culture. IGF‐I, but not estradiol, increased survival of MCF‐7 cells in the presence of either drug. Cell cycle progression and counting of trypan‐blue stained cells showed that IGF‐I was inducing proliferation in paclitaxel‐treated but not doxorubicin‐treated cells. However, IGF‐I decreased the fraction of apoptotic cells in doxorubicin‐ but not paclitaxel‐treated cells. Recent work has shown that mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphotidylinositol‐3 (PI‐3) kinase are activated by IGF‐I in these cells. PI‐3 kinase activation has been linked to anti‐apoptotic functions while MAPK activation is associated with proliferation. We found that IGF‐I rescue of doxorubicin‐induced apoptosis required PI‐3 kinase but not MAPK function, suggesting that IGF‐I inhibited apoptosis. In contrast, IGF‐I rescue of paclitaxel‐induced apoptosis required both PI‐3 kinase and MAPK, suggesting that IGF‐I‐mediated protection was due to enhancement of proliferation. Therefore, IGF‐I attenuated the response of breast cancer cells to doxorubicin and paclitaxel by at least two mechanisms: induction of proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis. Thus, inhibition of IGF‐I action could be a useful adjuvant to cytotoxic chemotherapy in breast cancer.

Insulin‐like growth factor (IGF)‐I rescues breast cancer cells from chemotherapy‐induced cell death – proliferative and anti‐apoptotic effects

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is known to influence the apoptotic response of cells; therefore, the antiapoptotic effect of IGF-1 on breast cancer cells was examined using different ECMs: laminin, collagen IV, or Matrigel. IGF-1 protected cells from apoptosis induced by methotrexate on all ECMs tested, providing the first evidence that IGF-1 protects against apoptosis in three-dimensional culture systems. These data provide the rationale to search for drugs that lower serum IGF-1 in an effort to improve the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of breast cancer.

Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) Alters Drug Sensitivity of HBL100 Human Breast Cancer Cells by Inhibition of Apoptosis Induced by Diverse Anticancer Drugs

The extent of apoptosis in vivo is correlated to the decrease in IGF-IR levels and, in turn, tumorigenesis in nude mice is correlated to the fraction of surviving cells. In syngeneic rats, a host response leads to complete inhibition of tumorigenesis. These findings establish, for the first time on a quantitative basis, the relationship between IGF-IR levels and the extent of apoptosis, as well as the relationship between the initial apoptotic event and the time of appearance of transplantable tumors.

Correlation between Apoptosis, Tumorigenesis, and Levels of Insulin-like Growth Factor I Receptors

Ketosis was associated inversely with serum insulin levels (P = 0.03).

Conclusion

Preliminary data demonstrate that an insulin-inhibiting diet is safe and feasible in selected patients with advanced cancer.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0899900712001864

As with insulin, inhibition of IGF-1 signaling has anti-cancer effects.

The Links Between Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cancer

The role of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) in programmed cell death has been investigated in vivo in a biodiffusion chamber, where the extent of cell death could be determined quantitatively. We found that a decrease in the number of IGF-IRs causes massive apoptosis in vivo in several transplantable tumors, either from humans or rodents. Conversely, an overexpressed IGF-IR protects cells from apoptosis in vivo. We also show that the same conditions that in vitrocause only partial growth arrest with a minimum of cell death, induce in vivo almost complete cell death. We conclude that the IGF-IR activated by its ligands plays a very important protective role in programmed cell death.

Multiple myeloma cell lines express functional receptors for insulin‐like growth factors (IGFs) and several cell types that make up the bone marrow microenvironment produce these cytokines. This suggests that IGFs may play a role in survival and/or expansion of the malignant clone within the marrow in patients with multiple myeloma. We tested the effects of these growth factors on myeloma cells challenged with dexamethasone. Dye exclusion and MTT assays demonstrated that both IGF‐I and IGF‐II protected the 8226 and dox‐40 myeloma cell lines and three primary myeloma cultures from dexamethasone‐induced cytotoxicity in a dose‐dependent fashion. Morphologic studies of target cells and their nuclei as well as DNA electrophoresis confirmed the IGFs afforded protection against dexamethasone‐induced apoptosis. Insulin also protected but was less impressive and required much higher concentrations. IGFs also protected against cycloheximide‐induced apoptosis but were ineffective against serum starvation, topoisomerase II inhibitors, or anti‐fas antibodies. IGF‐induced protection against dexamethasone was not associated with any alteration in quantitative or qualitative expression of BCL‐2, BAX or BCL‐X proteins. These data indicate that insulin‐like growth factors may play a role in maintenance of the malignant clone in patients with myeloma by protecting tumour cells from apoptotic death.

Resistance of cancer cells against apoptosis induced by death factors contributes to the limited efficiency of immune- and drug-induced destruction of tumors. We report here that insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) fully protect HT29-D4 colon carcinoma cells from IFNg/tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF) induced apoptosis. Survival signaling initiated by IGF-I was not dependent on the canonical survival pathway involving phosphatidylinositol 3*-kinase. In addition, neither pp70S6K nor protein kinase C conveyed IGF-I antiapoptotic function. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) with the MAPK/ERK kinase inhibitor PD098059 and MAPK/p38 with the specific inhibitor SB203580 partially reversed, in a nonadditive manner, the IGF-I survival effect. Inhibition of nuclear factor kB (NF-kB) activity by preventing degradation of the inhibitor of NF-kB (IkB-a) with BAY 11-7082 also blocked in part the IGF-I antiapoptotic effect. However, the complete reversal of the IGF-I effect was obtained only when NF-kB and either MAPK/ERK or MAPK/p38 were inhibited together. Because these pathways are also those used by TNF to signal inflammation and survival, these data point to a cross talk between IGF-Iand TNF-induced signaling. We further report that TNF-induced IL-8 production was indeed strongly enhanced upon IGF-I addition, and this effect was totally abrogated by both MAPK and NF-kB inhibitors. The IGF-I antiapoptotic function was stimulus-dependent because Fas- and IFN/Fas-induced apoptosis was not efficiently inhibited by IGF-I. This was correlated with the weak ability of Fas ligation to enhance IL-8 production in the presence or absence of IGF-I. These findings indicate that the antiapoptotic function of IGF-I in HT29-D4 cells is based on the enhancement of the survival pathways initiated by TNF, but not Fas, and mediated by MAPK/p38, MAPK/ERK, and NF-kB, which act in concert to suppress the proapoptotic signals. In agreement with this model, we show that it was possible to render HT29-D4 cells resistant to Fas-induced apoptosis provided that IGF-I and TNF receptors were activated simultaneously.

Diet contributes to over one-third of cancer deaths in the Western world, yet the factors in the diet that influence cancer are not elucidated. A reduction in caloric intake dramatically slows cancer progression in rodents, and this may be a major contribution to dietary effects on cancer. Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is lowered during dietary restriction (DR) in both humans and rats. Because IGF-I modulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis, the mechanisms behind the protective effects of DR may depend on the reduction of this multifaceted growth factor. To test this hypothesis, IGF-I was restored during DR to ascertain if lowering of IGF-I was central to slowing bladder cancer progression during DR. Heterozygous p53-deficient mice received a bladder carcinogen, p-cresidine, to induce preneoplasia. After confirmation of bladder urothelial preneoplasia, the mice were divided into three groups: (a) ad libitum; (b) 20% DR; and (c) 20% DR pius IGF-I (IGF-I/DR). Serum IGF-I was lowered 24% by DR but was completely restored in the IGF-I/DR-treated mice using recombinant IGF-I administered via osmotic minipumps. Although tumor progression was decreased by DR, restoration of IGF-I serum levels in DR-treated mice increased the stage of the cancers. Furthermore, IGF-I modulated tumor progression independent of changes in body weight. Rates of apoptosis in the preneoplastic lesions were 10 times higher in DR-treated mice compared to those in IGF/DR- and ad libitum-treated mice. Administration of IGF-I to DR-treated mice also stimulated cell proliferation 6-fold in hyperplastic foci. In conclusion, DR lowered IGF-I levels, thereby favoring apoptosis over cell proliferation and ultimately slowing tumor progression. This is the first mechanistic study demonstrating that IGF-I supplementation abrogates the protective effect of DR on neoplastic progression.

Mandatory FDA Disclaimer: Not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.

Mandatory FDA Disclaimer: Not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.